By Christian Weeks

From the April 2022 Issue

Building owners and facility managers have the unenviable job of figuring out how to respond to the growing demand for better indoor air quality (IAQ) while at the same time responding to ever more aggressive carbon reduction mandates. Add the need to protect building occupants from outdoor pollutants such as seasonal wildfire smoke and the challenge becomes even more complex.

The reason simultaneously improving IAQ, decarbonizing buildings, and increasing resilience to outdoor air pollutants is challenging is that buildings have traditionally relied on adding more outside air to improve IAQ.

In many climates, conditioning large volumes of outside air to maintain comfort while diluting indoor-generated contaminants like volatile organic compounds (VOCs) and carbon dioxide (CO2) for health is very energy intensive. HVAC is responsible for 36% of commercial building energy intensity in the U.S., and up to 40% of the HVAC portion of a building’s energy intensity is used to condition outside air.

The Covid-19 pandemic highlighted the tension between improving IAQ with more outside air ventilation and reducing building energy use intensity and carbon emissions.

At the beginning of the pandemic, the ASHRAE Epidemic Task Force (ETF) recommended maximizing outside air to decrease the risk of airborne transmission. This guidance was consistent with the old paradigm for improving IAQ that relies on energy-intensive dilution ventilation to clean indoor air. But as Dr. William Bahnfleth, chair of the ETF, told The Atlantic in September 2021, this guidance met immediate pushback due to concerns about surging energy use associated with conditioning more outside air. In November 2021, Johnson Controls and MIT published a study showing that increasing outdoor air ventilation rates to dilute the concentrations of infectious aerosol particles indoors, while effective, “is often much more costly than other strategies that provide equivalent particle removal or deactivation.”

Studies like the one from JCI/MIT led ASHRAE to update its Covid-19 guidance in January 2021 to address the energy penalty concern. The new Core Recommendations for Reducing Airborne Infectious Aerosol Exposure are based on the concept that ventilation, filtration, and air cleaners can be combined flexibly to achieve exposure reduction goals while minimizing associated energy penalties. According to the Core Recommendations, building operators should use combinations of filters and air cleaners that achieve MERV 13 or better performance for recirculated air, maintain at least required minimum outdoor airflow rates, and select control options, including filters and air cleaners, that provide desired exposure reduction while minimizing associated energy penalties.

The Core Recommendations also state that the effectiveness of filtration, air cleaners, and ventilation can be measured using an equivalent air change per hour (eACH) metric in place of the traditional ACH metric that only focuses on outdoor air and does not account for filtration and air cleaning.

This updated ASHRAE guidance provides building owners and operators with a roadmap to improve IAQ and achieve building decarbonization and resiliency goals simultaneously. We call this Sustainable IAQ: healthy and resilient indoor air quality achieved energy efficiently and cost-effectively.

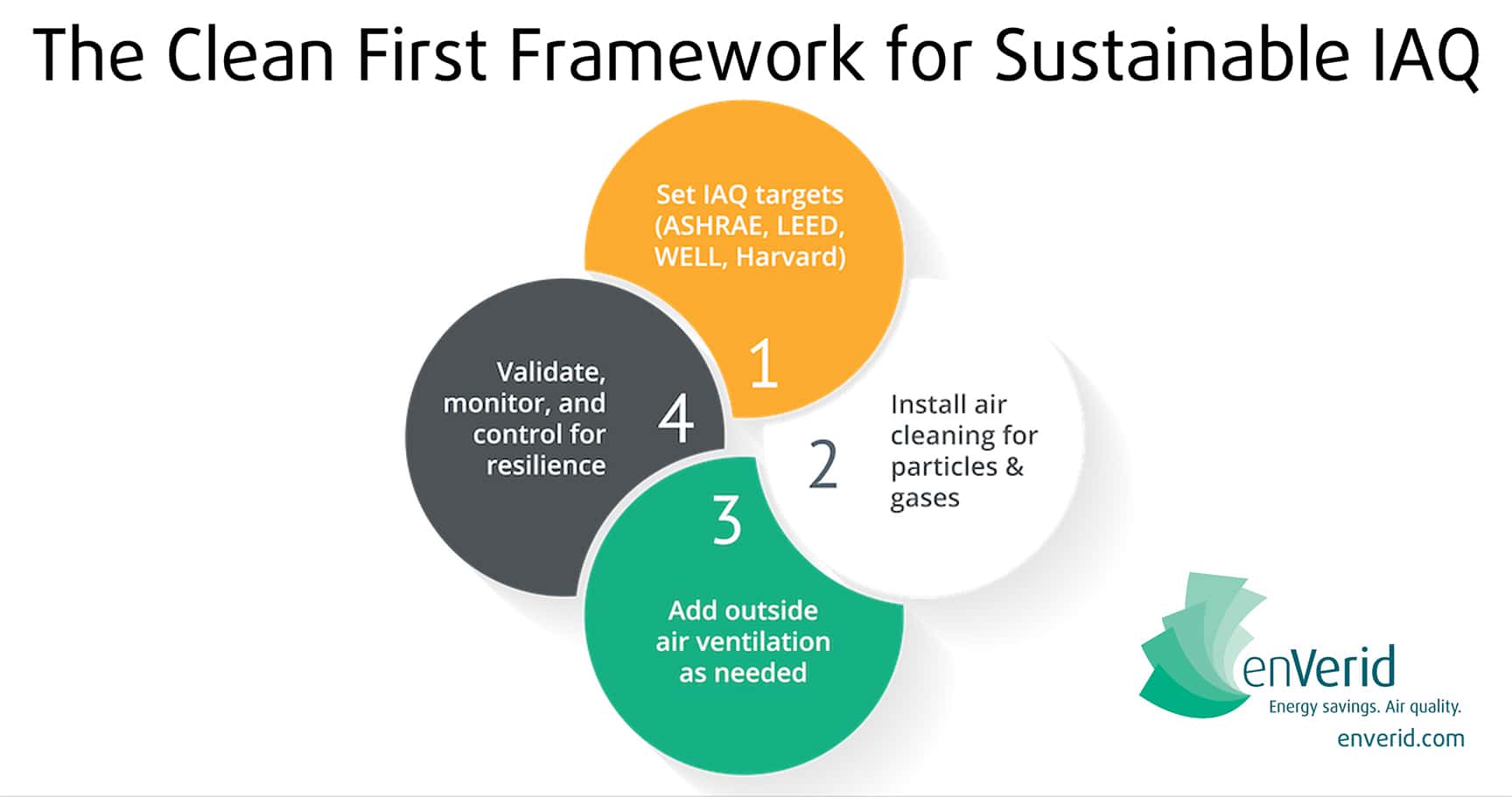

The key to achieving Sustainable IAQ is deploying layered filtration, air cleaning, and ventilation strategies and integrating continuous IAQ monitoring and dynamic building controls to ensure IAQ targets are maintained with maximum energy efficiency and resiliency. This layered “Clean First” approach is the key to low-energy, high-IAQ, resilient buildings of the future.

The Clean First framework includes four steps designers and operators can follow to achieve Sustainable IAQ—though the implementation order may be different for new and existing buildings.

Step 1 is to define indoor air quality goals. Many buildings have not taken this basic step, but we expect this to change as more buildings focus on health and wellness and adopt IAQ goals based on guidelines from ASHRAE, LEED, and WELL. IAQ goals may be stated in terms of VOCs, CO2, or particulate matter (PM) levels.

Step 2 is to maximize the amount of air cleaning for recirculated air. Tried and true technologies include high efficiency filters for PM and bioaerosols (high MERV and HEPA filters) and sorbent filters for gaseous contaminants. According to ASHRAE, properly installed and maintained MERV 13 filters are 89.93% efficient for airborne droplet nuclei the size of SARS-CoV-2. Combining filters for PM/bioaerosols and filters for gases is key to addressing the full spectrum of contaminants.

Once we have cleaned as much of the indoor air as possible, Step 3 is to determine optimum outside air rates to achieve IAQ targets and maintain building pressure. This can be done using ASHRAE’s IAQ Procedure within Standard 62.1, which is a performance-based ventilation design method to determine the amount of outside air needed to achieve specific IAQ targets accounting for the effectiveness of air cleaning. Addendum aa to ASHRAE 62.1-2019 makes applying the IAQ Procedure much easier for consulting engineers by prescribing a minimum list of Design Compounds and Limits.

The final Step is to validate, monitor, and control IAQ to ensure targets are maintained. This can be done through IAQ testing and continuous monitoring. Ideally, IAQ monitoring is integrated with control systems to automate and optimize air cleaning and outside air ventilation for efficiency and resiliency.

To show the benefits of this Clean First approach, we calculated the energy, cost, and carbon impacts of two strategies for mitigating airborne transmission of Covid-19 for a 600,000-square-foot office building in metro-Boston. The analysis summarized in the charts in the article (see below) shows that minimum outside air per the ASHRAE 62.1 IAQ Procedure combined with high efficiency particle filters for Covid-19 mitigation and sorbent filters for gaseous contaminants delivers comparable equivalent air changes to an increased ventilation scenario (5.25 vs. 5.45 eACH) at less than half the annual operating cost and less than a third the annual carbon emissions.

As Dr. Joseph Allen from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health wrote recently in STAT, “Our climate and healthy building goals do not have to be in conflict; it is possible to have energy efficient buildings that provide healthy indoor air.” According to Dr. Bahnfleth of the ASHRAE ETF, “The future of really good indoor air quality is going to be alternatives to ventilation, so we don’t have to rely on outside air for everything.” A Clean First approach is how we can get from current state to future state.

Weeks is the CEO of enVerid Systems, a leader in indoor air quality and energy efficiency. With over a decade of experience in energy efficiency and indoor air quality, he is passionate about helping building owners and operators achieve their energy efficiency and indoor air quality goals.

Weeks is the CEO of enVerid Systems, a leader in indoor air quality and energy efficiency. With over a decade of experience in energy efficiency and indoor air quality, he is passionate about helping building owners and operators achieve their energy efficiency and indoor air quality goals.

Do you have a comment? Share your thoughts in the Comments section below, or send an e-mail to the Editor at acosgrove@groupc.com.

![[VIDEO] Collect Asset Data at the Speed of Walking a Building](https://facilityexecutive.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/maxresdefault-324x160.jpg)