By Usha Tyson, P.E.

From the April 2021 Issue

Keeping up with regular inspections, testing and maintenance of sprinkler systems in buildings is vital to ensure proper operation. The International Building Code (IBC) and NFPA 101: Life Safety Code (LSC) are specific codes that dictate the required active fire protection systems for buildings based on occupancy type and square footage. Building code provisions published by the International Code Council (ICC) and National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) outline the minimum construction and life safety requirements for structures based on use and size.

Active fire protection systems include: automatic fire sprinkler systems; fire alarm and detection systems; smoke control systems; and others that detect a fire, alert occupants, and/or help control or extinguish a fire.

While considered an active system, an automatic fire sprinkler system may be perceived as an invisible form of protection after its installation and acceptance testing— one where you “set it and forget it.”

The typical sprinkler system found in a conditioned space, such as an office building, is a wet-pipe sprinkler system. This consists of a piping system throughout the floor which contains water. Sprinkler heads (either standard or quick response) activate upon detection of heat and release water. Many think every sprinkler head opens as a result of activation of a sprinkler system, but this is almost never the case. Sprinklers are localized, and a sprinkler head will only operate once the thermal element is triggered by heat from a fire.

An alternate type of sprinkler system is a dry-pipe sprinkler system. This type is utilized when the building (or areas of the building) are subject to freezing temperatures. Some structures may contain both systems. For example, a wet-pipe sprinkler system may protect the main building, and a dry-pipe system may be installed in the loading dock or open parking garage. For the dry-pipe system, the piping system will only fill with water once the sprinkler head is activated. Therefore, there is a delay in water delivery, which is accounted for when the sprinkler system is designed.

NFPA 25, the Standard for Inspection, Testing and Maintenance (ITM) of Water-Based Fire Protection Systems, requires monthly, quarterly, semiannual, and annual inspections and testing for fire sprinkler systems.

NFPA 25 notes that responsibility falls on the building owner or designated representative to ensure required inspections and testing is met. While a contractor may be hired for the actual inspection or to conduct testing, the ultimate onus is on the building owner. It’s important to conduct visual inspections often, not only when there is an apparent deficiency. Things to look for include leaks, foreign objects tied on sprinklers, and sprinkler piping. For example, a cloth or rag wrapped around a leaky fitting is not an appropriate solution. Visual inspections can be conducted by facilities staff and don’t necessarily require hiring a contractor. NFPA 25 requires ITM be performed by qualified personnel, which doesn’t always mean licensed, but does mean staff should be trained.

Trained building personnel are capable of performing a number of ITM tasks. With minimal training, facilities staff can perform visual inspections to check for visible signage in the sprinkler riser room, leaks, corrosion on sprinklers, physical damage, loss of fluid in glass bulbs, and paint on sprinkler heads. Often, damaged sprinkler heads may be overlooked, or dismissed, but bent deflectors can severely impact the water distribution pattern and sprinkler effectiveness. Paint on sprinklers is one of the biggest deficiencies found when conducting a visual inspection. Similar to smoke detectors, sprinkler heads should be covered where painting is conducted. Paint may insulate the thermal element of the sprinkler, affecting operation.

Quarterly inspections should include visible observations of gauges, tamper switches, and waterflow alarm devices. Annual inspections should include confirming proper signage for hydraulic information is provided and visible for each sprinkler riser. Hydraulic signage (also referred to as nameplate) should include the system’s original design information, including: design density; design area; and number of sprinklers on the system. The nameplate should also identify: date of installation; area or floor protected by the riser; and water pressure at the base of the riser. In addition, a visual inspection should ensure pipes and sprinklers aren’t exhibiting leaks and that spare sprinklers are provided.

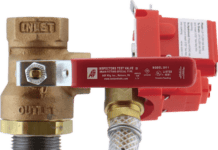

For required testing of the sprinkler system per NFPA 25, it is recommended to get a professional involved. As sprinkler systems can remain idle for years, testing is the main method of verifying performance. Test switches are specifically required in order to test functionality of waterflow alarm switches and tamper switches without causing too much disruption. These tests are required semi-annually.

For inspections, testing, and maintenance managed by a contractor, it is recommended that facility management occasionally audit the service contract to ensure NFPA 25 requirements are met. It is also an opportunity to ensure that inspection tasks handled in-house are excluded. Keep a track of monthly, quarterly, semiannual, and annual inspections. If an event is to occur, having the documents handy may prevent legal woes.

Sprinkler systems are a life safety feature found in almost every commercial building. But, a system that has not been maintained offers a false sense of security. The only way to achieve compliance is to perform required inspections, testing, and maintenance.

Tyson has been a consultant at Jensen Hughes for 15 years. She has extensive experience in fire alarm and life safety design, fire alarm inspection and testing, evaluation and review of automatic sprinkler design, and building code analysis. Tyson earned her Bachelor’s degree in Fire Protection Engineering from the University of Maryland.

Tyson has been a consultant at Jensen Hughes for 15 years. She has extensive experience in fire alarm and life safety design, fire alarm inspection and testing, evaluation and review of automatic sprinkler design, and building code analysis. Tyson earned her Bachelor’s degree in Fire Protection Engineering from the University of Maryland.

Share your thoughts in the Comments section below, or send an e-mail to the Editor at acosgrove@groupc.com.

Want to read more about facility management issues?

Check out all the recent FM Issue columns from Facility Executive magazine.

![[VIDEO] Collect Asset Data at the Speed of Walking a Building](https://facilityexecutive.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/maxresdefault-324x160.jpg)